Group Show: The Other Side of the Mirror is HomeGalerie Peter Kilchmann

Zahnradstrasse, Zurich

Vlassis Caniaris, Willie Doherty, Beatriz González, Leiko Ikemura,

Teresa Margolles, Dagoberto Rodríguez, Adrian Paci, Shirana Shahbazi in collaboration with Anne Morgenstern, Didier William and Artur Zmijewski

The Other Side of the Mirror is Home

Opening: Friday, September 1, 6 - 8 pm

Zahnradstrasse 21, 8005 Zurich (Maag)

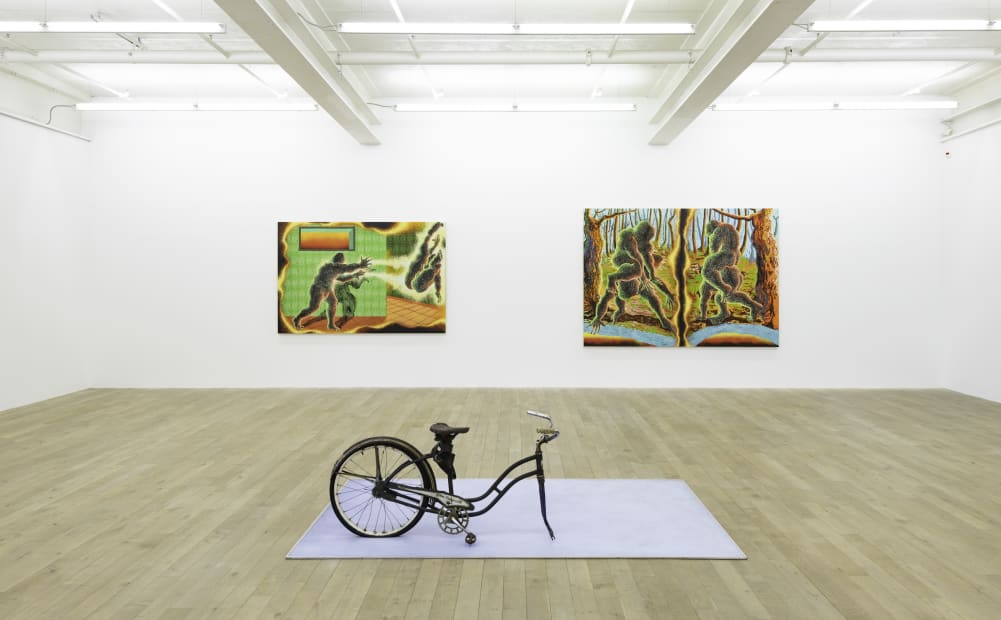

Galerie Peter Kilchmann Zurich is pleased to present a group exhibition dealing with themes of migration, movement, displacement, and refuge. As of this summer, official estimates of the current number of refugees and displaced persons globally stand at a record high—reflecting the ongoing crises on all seven continents today. This exhibition presents ten artists whose work directly engages the realities of the present as it emerges from the longer span of history, drawing from the experiences and memories of the individual and the collective. The exhibition’s title is adapted from Didier William’s diptych in the exhibition, Chevalier: The Other Side of the Mirror is Home, 2023, which appears to be split in two by a tectonic force. In the artist’s own words, this work attempts to “map out the space between here and home, whatever either of those spatial conditions might constitute in real time. This painting actually imagines them to be in many ways symmetrical.”

Also in the exhibition is Didier William’s (*1983, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, based in the US) painting I Wanted Her to Kill Him, I Know Why She Didn’t, 2023, which continues the artist’s ongoing investigation of language, aesthetics, tradition, trauma, and autobiography through a visual language that is at once imaginative, mythological, and metaphysical in perspective. These two large-scale works present the artist’s signature marriage of print-making, collage, and wood-carving techniques to describe scenes drawn from a place of memory. By reimagining scenes from the artist’s childhood, they transfigure familial memory into the realm of mythology. The result is a brilliant connection to generational memory that gives form to the varying complexities of diasporic identity while also discarding of the kind of boundary that arbitrarily designates nation or possession. This marks the first time William’s work are featured at Galerie Peter Kilchmann, ahead of his forthcoming solo exhibition at the gallery in June 2024.

In the center of the first exhibition space the prominent installation Untitled (Bicycle), 1974, by Greek artist Vlassis Caniaris (1928-2011, Athens, Greece) explores the theme of the status of migrants and immigrant workers. Caniaris left his home country of Greece due to the political climate under the reigning Junta following a controversial exhibition in Athens in 1969. He closely experienced the initial enthusiasm of westward migration within Europe which after the oil shock of 1973 promptly was followed by protectionism and xenophobia. The sculpture belongs to Caniaris’ most significant group of works, Gastarbeiter – Fremdarbeiter (foreign worker), that he created in Berlin between 1971 and 1976 and was exhibited at the 1988 Venice Biennale and Documenta 14 in 2017 amongst other. Untitled (Bicycle) embodies not only a simple means of transportation but also the poverty and social marginalization that migrants like Caniaris’ experienced in Berlin. To create his work, he depended on inexpensive materials and found items that he appropriated and repurposed. The run-down bicycle stands on a contrasting light-blue wood panel standing as a metaphor for hope.

In opposition, in Adrian Paci’s (*1969, Shkoder, Albania) series Home to Go, 2001, a migrant figure humbly carries on his back an overturned roof, almost transforming it into a wing-like shape. He thereby, like Caniaris, produces a similarly poignant metaphor for the migratory experience. It is a literal transition from one homeland to another and the weight this experience bears, both figuratively and literally.

Shirana Shahbazi (*1974, Tehran, Iran, lives in Zurich) and Anne Morgenstern (*1976, Leipzig, Germany, lives in Zurich) developed the Hardau series in close cooperation. In a first step, the two artists created portraits in their predominantly migrant neighborhood, which then in a second step were spatially staged in the studio and photographed again. This process creates a third, fragmented space that cannot be clearly located, in which the people portrayed move at times confidently, at times thoughtfully. The works were developed in connection with the INES Handbuch Neue Schweiz (2021, Diaphanes Verlag, Zurich), for which Shirana Shahbazi designed and was responsible for the picture editing. "The book offers a position statement on ongoing post-migrant, anti-racism and intersectional debates and visions and combines essays, biographical stories, literary texts, an extensive glossary and a variety of artistic image contributions" (blurb). INES Institut Neue Schweiz is a think and act tank based in Bern and is committed to the one Switzerland of the many - for everyone who is here and who is yet to come.

Leiko Ikemura (*Tsu City, Mie Prefecture, Japan, lives in Berlin) considers herself an amalgam of migration, travel and cultural exchange. Having spent many years in different locations, her deep and multilayered oeuvre is rooted in her biography, combining Japanese Shintoism and the European canon of artistic traditions, amongst others. She herself has become a bridge between different cultures, which are oftentimes inhabited by stark contrasts. At first glance the subjects in her series Artists, Popes & Terrorists, 2008 appear like an anonymous group of individuals. However, in the artist’s work, they provide a projection space for hope, fear, the mythical, and the whole spectrum of emotions, uncertainties and the unknown.

Artur Zmijewski (*1966, Warsaw, Poland) points out how we confront the aspect of the unknown and our urge to deconstruct it. In 2018, he staged the photo series In Between, in which he measures the bodies of migrants and asylum seekers in Paris in a naive anthropometric fashion, referencing outdated ethnographic propaganda. Maybe by cataloguing and quantifying the unknown we can create an illusion of self-comforting control? The exhibition entails four black & white photographs that bleakly document the poverty and hopelessness of the portrayed men.

Teresa Margolles (*Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico, lives in Madrid) also took pictures of migrants as part of an individual documentation. However, she displays the human tragedy of the refugees and migrants in a more personal fashion. The installation La Entrega (The Delivery) is related to Margolles’ research in the border region between San Antonio de Táchira, Venezuela and San José de Cúcuta, Colombia, where she engaged with the sites and consequences of forced migration. Since 2017, Margolles has developed a series of actions with the local Venezuelan refugee community, in order to strengthen their cohesion and the participants' own sense of identity. La Entrega belongs to the major group of works titled Estorbo (Obstruction) for which the Margolles involved a total of over 180 young Venezuelan men who work in the area as "carretilleros" and "trocheros" (load carriers). The cube is the result of a performative act that Margolles developed from a temporally displaced combination of dialogue and interaction. A Venezuelan migrant told the artist his respective story and then, as a symbol of his physical labor, gave her the t-shirt covered with the sweat from his activity. In a performance at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá in Colombia in 2019, the t-shirt was cast into the concrete cube, while engraving the initials of the participant into the cubes' surface. The cube is accompanied by a life-size portrait of the participant, captured in the fragile moment when he delivers his t-shirt. Also in Colombia, Margolles created the work Album de Familia, at the frontier bridge Simón Bolívar. Margolles took two polaroids of Venezuelan migrant families while they were crossing. The family kept one of the photographs and the artist kept the other. The memory of their passage when leaving Venezuela behind is manifested in the polaroid.

Beatriz González’s (*1932 Bucaramanga, Colombia, lives in Madrid) has also witnessed the tumultuous political and economic hardship that caused Margolles’ to explore the migrant issue. Gonzàlez’ motif of the displaced figure - one that is forced to leave its home region - is a common narrative of her series Desplazamientos forzados (Enforced displacements). When in 2015 the Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro expelled more than 6‘000 Colombians, who used to live near the Colombian border, the print media is overflowing with images of families, as well as single men and women, crossing the border rivers Táchira and Zulia with their possessions. Based on those images, motifs like groups of people carrying heavy packages, mattresses or even closets on their shoulders, are repetitively processed by the artist within her paintings and drawings. By reducing the color and simplifying the form, the figures are transformed into an iconic symbol.

Cuban artist Dagoberto Rodriguez (*1969, Havana, Cuba) uses a similar visual technique to make a subtle but powerful point about our deluding perspectives. Zooming out from the individual and focusing on the larger image, he puts a focus on the consequences of war and the spread of refugee camps due to recent tragedies. The exhibition contains three works on paper from his Refugee Camps series. In 2017, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees, mostly Muslims, have fled from a Burmese army offensive and now live crowded together in dire sanitary conditions in Bangladesh. Zaatari is located in Jordan and is the largest Syrian refugee camp in the world.In Havana, the locals who meet in the old city of the port, hope to leave the island and to escape the political, social and economic crisis that has beset Cuba. They feel just as imprisoned, although this part of Havana is not strictly a refugee camp. The aesthetic and almost playful dimension of the wide shots seen from the sky engages the viewer in a paradoxical way. The Lego motif keeps the narrative at a distance and withdraws the viewer from an immediate understanding of the subject.Relationships of human hostility are at the heart of the Refugees Camp series. Rodríguez highlights the strategies of power at work in the repression, control, and domination of the social body.

Finally, the exhibition contains works by Willie Doherty (*1959, in Derry, Northern Ireland) who has explored the conflict in Northern Ireland through his films and photographic works that are bound together by the urban landscape. Between (Where the Roads Between Derry and Donegal Cross the Border), 2018, continues Doherty's investigation into the consequences of conflict and trauma around the world, particularly in the zone between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. These moments of rain-soaked calm are not only testaments to a past conflict, but they are simultaneously haunted by their potential future. The achievements of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement are being threatened by Brexit and we experience the fragility of peace and the undoing of civilized conduct amongst state actors. The monumental achievements in overcoming large-scale violent conflicts in the European continent of the last eighty years are actively threatened and borders between countries are solidified again.

Doherty’s work Home Waiting, 2016 is a film still from a video that shows a lonesome young man wandering around the urban environment of an unknown city. In the video Doherty follows the alienated figure and the protagonist seems to have no connection with the places in which he ends up. It seems as if he is trying to protect himself against a potential threat. Home (Waiting) revolves around the refugee issue and offers scarce tangible opinions about the young man's health and security or about the way in which such an individual can be looked after under conditions of danger and threat. The work offers no context and conveys a feeling of vulnerability and uncertainty.

For further information please contact Thomas Ruettimann: thomas@peterkilchmann.com

-

Didier William, Cheval: the Other Side of the Mirror is Home, 2023

Didier William, Cheval: the Other Side of the Mirror is Home, 2023 -

Vlassis Caniaris, Untitled (Bicycle), 1974

Vlassis Caniaris, Untitled (Bicycle), 1974 -

Beatriz González, Desplazamiento horizontal (Horizontal displacement), 2016

Beatriz González, Desplazamiento horizontal (Horizontal displacement), 2016 -

Willie Doherty, Home (Waiting), 2016

Willie Doherty, Home (Waiting), 2016 -

Dagoberto Rodriguez, Rohingya Refugee Camp, 2023

Dagoberto Rodriguez, Rohingya Refugee Camp, 2023 -

Teresa Margolles, La Entrega (The Delivery), 2019

Teresa Margolles, La Entrega (The Delivery), 2019 -

Artur Zmijewski, In Between, 2018

Artur Zmijewski, In Between, 2018